Talking about weather

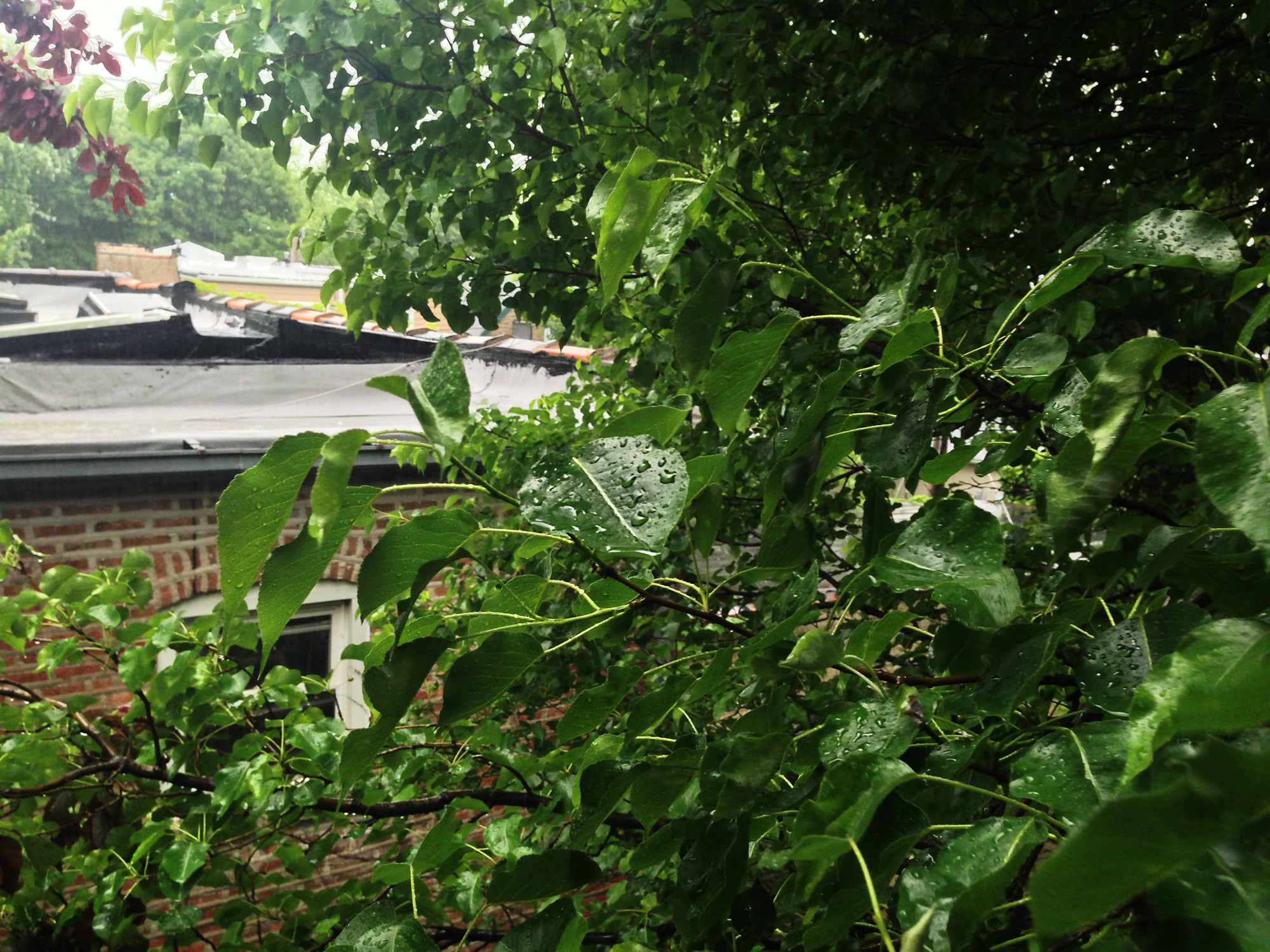

We’re at the tail end of a long stretch of warm weather storms. Just like spring, summer came early — the hot, muggy days expected of July went ahead and showed up in late May. Fans are set up in every room. Beds have been stripped of their comforters. Ice cubes clink in sweaty glasses of water. And every day brings a rain shower of varying intensity. Today, the thick white cloud cover overhead is slowly shifting to gray. Sharp gusts of cool wind burst through dense canopies as if to say, “Get ready.”

Before I moved to Chicago, my understanding of summer storms was sorely limited and essentially flawed. The “rainy season” in Southern California mostly comprised of a few weeks in November when the ground goes damp and everyone forgets how to drive. Here in the Midwest, I’ve learned the extreme weather season lasts all year.

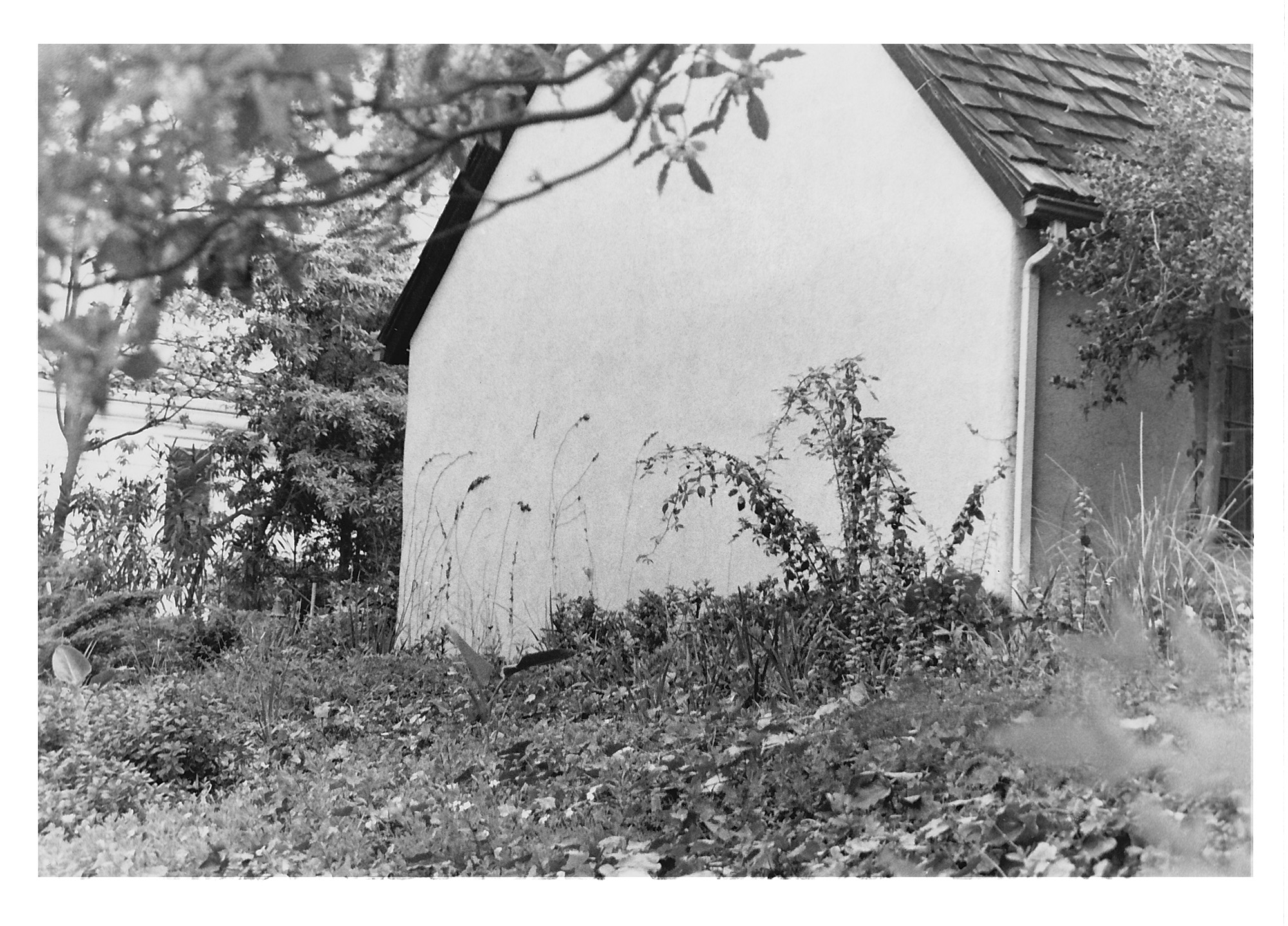

My first big warm weather storm happened during my first summer in Chicago. I was in college at the time and paid $270 a month to live two blocks from campus in a sunroom with white-framed windows on three walls. The subsequent winter would see me huddled by a space heater, attempting to ignore the frost growing on both sides of my single paned glass. But in the warm season, windows and curtains stayed open to let the breeze flow through. The room was my refuge in the trees. I spent much of that first summer sitting in the window sill, watching the lazy handful of neighborhood kids and graduate students jaywalk three floors below.

One afternoon in my bedroom, I noticed the light change. The buttery yellow walls had begun to glow a hazy orange. I leaned closer to the window screen and struggled to focus my eyes on the sky, sidewalk, brick buildings across the street. Everything was bathed in the eerie orange light, deepening rapidly. The air hummed with electricity. The cloud cover thickened and before long, the sky let loose an angry spew of hail that turned green lawns white and rattled violently against our cement facade. As quickly as it came, the hail slowed and then stalled, melting away and taking the thick orange sky with it. Hot, wet asphalt and leaves fat with the weight of water were left behind as the only evidence of the storm.

In the years since, there have been many more hailstorms, some worse than others. We’ve had thunderstorms that blew out power for entire neighborhoods, powerful stabs of wind that felled the oldest trees, curbside flooding that turned intersections into lakes. There was even that year when we were first introduced to the legendary derecho. A this point, I’ve had a lot of experience with this city’s intense weather. But every time the sky darkens and the winds ripple through wildly swaying trees, I’m still surprised.

I suppose it’s the city’s brush with untamed nature. We don’t have craggy mountains to arch our necks at, or vast oceans to dive, or deep forests to wander. Chicago’s natural beauty has been largely leveled to make way for historic feats of architecture, temples of culture and academia, and a few hundred lovingly tended urban parks. But the weather is our great equalizer. We’re all cold on the hundredth straight day of freezing temperatures in April, and we’re all in awe of the uncontrollable power of a wild summer storm. It doesn’t matter how much we try to insulate ourselves with society and technology. One way or another, nature always overpowers, stuns, delays, distracts, reroutes, impresses, terrifies, and drenches us.

The breeze outside picks up speed and the windchimes on our back porch sing louder and more often. A distant rumble of thunder echoes, and the skies churn from bright white to a swirling gray. When today’s storm breaks, I have my face pressed hard to the glass. I watch in awe as the army of droplets fall, and as the wind blows unknowable patterns in the soaked and shining streets.